By Emmie Chacker

There’s this surprise when I tell people, offhand, that I was born outside of the country. Or that my parents aren’t Chinese. Or that I cannot speak the language. Two women at 15th Street Station on the Market-Frankford Line ask me for directions—opening in Mandarin. Because that’s the extent of what I know about what they’re attempting to communicate to me, all I can say is, “I don’t speak,” clearly, and then nod when they ask, “Snyder?”

I could point to the city where I was born on a map painted on the wall of the elevator bay of a 3-star hotel in New Jersey, across the bridge from New York City.

I can’t pronounce the name. I can tell you it’s in the South-Central region of China.

I ping-pong between wanting to remember my infancy in China and wanting no origin at all.

I didn’t know how to tell my friends, who I shared a fluffy queen bed with in that hotel room overlooking a car park and the highway, that the part I leave out is how strangely I hold this history. At arm’s length, with reverie, detachment.

“Kunming. There.” That is where I was born.

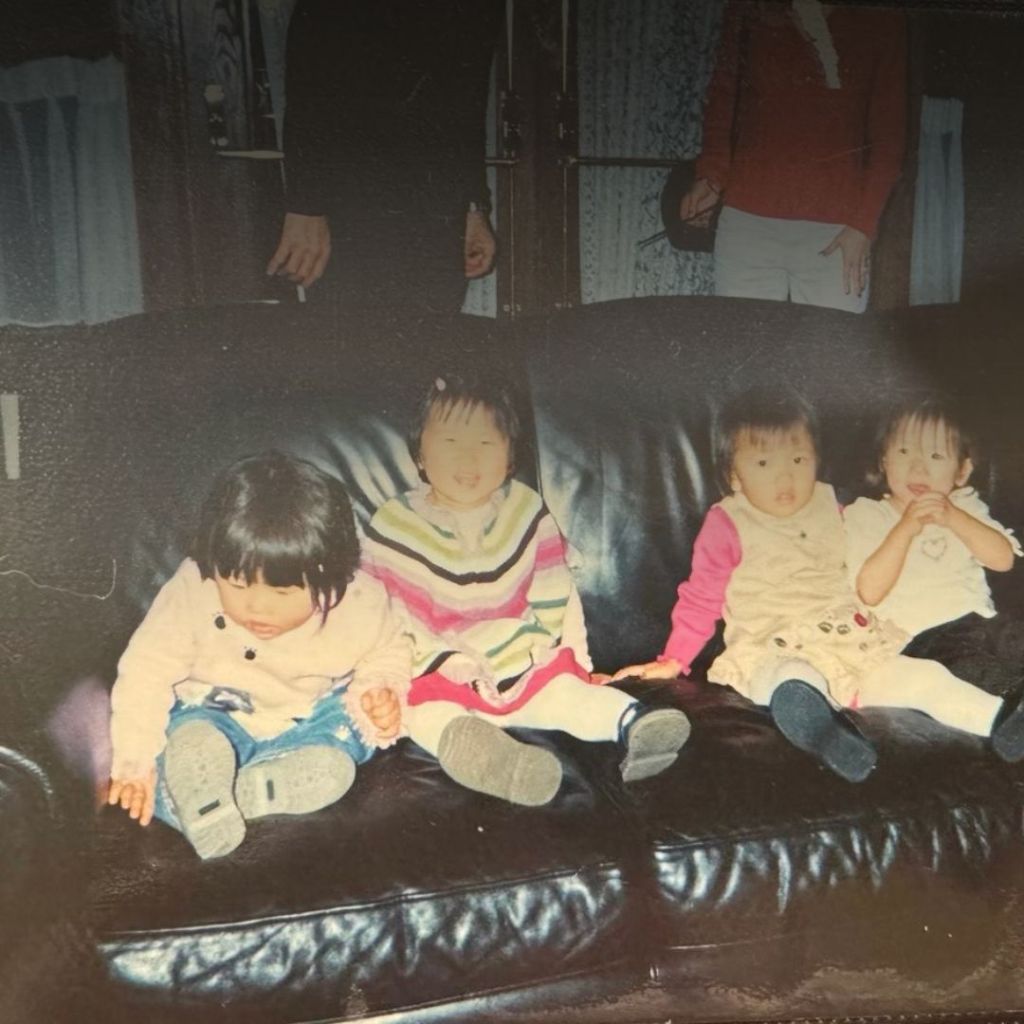

You were a fat-faced infant with pneumonia.

Infants can’t form memories the same way older children can. And even far past infancy, there are chunks of my life missing—oddly, blurred over, happily absent. My first phase of life is a lost letter, unretrievable and blank—but isn’t it for every baby? My adoptive/real/forever/white/American parents met me on November 10th, 2003, thirteen months after I was born.

The name of the city I’m from is called “the city of eternal spring.” A nickname: 春城.

And when I was one week old, I was left on the steps of a flower shop in that city. A flower market in eternal spring. I’d imagine birth was violent. As all are. I imagine I was swaddled in a blanket and cold on the stoop and everything was bundled in an unremarkable October during that eternal spring.

No doubt not the first nor the last infant placed gently on a stoop, crying after a set of arms walking away, that same week.

China, the CCP, said no second children. It was determined that the population had grown too large too fast, and the solution was: only one child. The people, staring at their culture (this is the story you are told, and the numbers say that in 1999, four years before you, 98% of Chinese adoptees were girls), did not want a healthy baby girl.

So this is what is assumed: You are here now because you were a second or a spare or a girl. It was inevitable. And you are lucky. It doesn’t matter. You are lucky. Western Medicine fixed the nasty case of pneumonia you had at twelve months. Your illness was acute. Would the new parents have wanted you if you had a cleft lip like Zaya? Surely, they would have, no?

At twenty-two years old, I’ve taken to the book character Zaya, “Little Rabbit.” Good Citizens Need Not Fear, a collection of short stories by Maria Reva featuring Zaya, her cleft lip, and the Soviet orphanage where she spent her early life. Reva writes Zaya in a prose that is polemic and beautiful, but the way she describes the communist orphanage sounds more like a horrible fairytale:

The baby house sits tucked behind a hill, out of sight of the village and the town…The main hall of the baby house has bright windows and three rows of beds, and a sanitarka who makes rounds with a milk bottle.

__________

The Kunming Children’s Welfare Institute was the home for the infants before they went into the foster village outside of the city at three years of age.

Mission and Services: Operating on the principle of prioritizing children’s welfare, the institute has developed a robust framework to protect the rights of its young charges. It offers round-the-clock admission and medical care, striving to uphold their rights to survival and protection.

All I remember about the tour of the Kunming Children’s Welfare Institute (this was when I was four, my parents and I were back in China to pick up my sister, and in Kunming to sightsee) is a spiral staircase, and being told we could not walk the halls. I remember a room with a grid of empty cribs. It had wooden floors, in my memory.

If memory brings the past to us (to life), I’m trawling in a dead sea. I don’t remember much. When I do, I doubt.

If you can’t remember it, did it even happen? Was I ever there, at four or at four weeks?

A personal history is inconsequential, but fundamental.

Imagine this—you spend a long time ignoring something basic: I am from. You grow. It does not. It hides in the corner. It grows legs. It falls on itself. It’s very ignorable. The scar will always take up the same portion of your wrist. Lucky girl.

From the age of four to fourteen, I thought of it very little.

Here’s one thing I do remember–I was touring a local high school in 8th grade, considering where to attend the next stage of schooling. I was walking between school buildings, and a student walked up to me–fast, excited, and said something in rapid Mandarin. I now assume he was an international student at that suburban school where none of the students spoke Mandarin, or at least not to him.

“I’m sorry, I don’t speak…” And that was that.

My family went on vacations. One year, to Monterey, California, where a wine-drunk woman thought I was my father’s wife, when I was twelve. I had to assume, then, because I was a East Asian girl and he was a white man, and I was sitting across his lap as twelve-year old daughters do.

My mom used to be uncomfortable when I attached myself to older East Asian women who flitted through my life. My father practiced his Asian cooking and his facsimile of the Chinese language.

He never learned, only parroted what he thought he heard in American films and such, so his attempts always sounded like grating mocking (“Chi ching chong,” etc).

You were an adorable child.

Remember, I had fat cheeks. I had a bowl haircut. I scraped my knees and picked at my mosquito bites until they bled and scarred. I tripped up an escalator in Rethymno, Crete, when I was fourteen, and there’s still a keloid where my ankle meets my leg, at the low shin.

So maybe I am lucky––almost every scar on my body is accounted for.

- Floor burn from the giant slide in Smith Playground.

- Concussion at the water slides in central Pennsylvania’s Costa’s Waterpark.

- My Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine as a card-carrying member of the born in a country fighting TB in the aughts club.

But there’s one that came before anything I can remember at all. For many years, I thought it was a birthmark. An unnoticeable mark like the Milky Way where no arm hairs grow, that meets the shadow of my inner wrist bone over the top of my forearm.

Now, I think it could be a very old scar from that first home.

My mother and I watched a documentary when I was nineteen about adopted girls from China. All I can remember about the documentary is apparently some infant was tied to their crib with twine so they wouldn’t smother themselves in their sleep. Was this common practice?

Is my pale right wrist a birthmark?

It was a white mark by the time I was thirteen months, and I crossed the ocean, no matter what made it.

All my newer scars, deep enough to stick around, are keloids—raised, dark, angry. But I remember them.

In preschool I wrote an “I am from…” poem. We were given a set of prompts and told to answer them with poetic language in the first grade. Poetry to a first grader is word salad-soup, and in my memory soup there is the idea that I was from Philadelphia and did not mention that I was from Kunming and there was little else to it.

When I can’t speak the language, I ask nobody: Whose face matches the way they were raised? I could have learned. I still want to. But I am not learning Chinese right now.

Zaya reappears and becomes a fraudulent beauty queen, her cleft lip fixed, in a later short story in Good Citizens, after she has run from her first home.

On a cold afternoon this October in Philadelphia, I found the website for my old Children’s Welfare Institute. The floors are not wood, as I remember. Maybe they’ve simply redone them, now that the children that arrive there are different. Eighteen years have passed. After the end of the One Child Policy in 2015, orphanages saw more and more boys and more and more “unhealthy” children.

2015 post on the Kunming Children’s Welfare Institute Website [昆明市儿童福利院]:

5月11日、12日,椰岛造型美发机构结合自身资源优势,到我院做理发和美容美发

志愿服务活动.

On May 11th and 12th, Yedao Hairstyling and Hairdressing Institution combined its own resource advantages to provide hairdressing and beauty salon volunteer services in our hospital.

The case for remembrance arises in the slow-loading website for a place I have, in all practicality, never been. (Though I have official documents stating I was there for twelve months). A scar on my wrist, a language I never learned. This city is getting cold, and spring is half a year away. The calendar says that my Gotcha Day is still on November 10th, to be recognized annually. I don’t mark it on my calendar, but I remember the day.

—

BBC World News [09/06/2024]:

China has announced that it is ending the practice of allowing children to be adopted overseas.

So here I am.