By Alan Jinich | Photos by Alan Jinich

Penn After Midnight is a series of vignettes—late night tales—strung together in the winter and spring of 2022. In the early morning, I used to ride my bike around campus in search of the people who kept campus breathing: Amber, a highrise security guard; Nasir, the West and Down nightclub bouncer; and many more in places like McDonald’s, the police station, neuro ICU, and even my first-year dorm room. All of these places have changed from what they were one year ago. McDonald’s, once a late night haven, is now demolished. West and Down shut down. Amber is no longer a security guard. We’ve all been replaced through the cycles of university life and I’m no exception. But the shoes that we filled are still there, fossilized in our city that doesn’t sleep.

Computer Beeps and Happy Meals

The only letters still lit are the “L and the “S.” There’s no glow in the rest. A-O-K by Tai Verdes plays in the background, but no one seems to hear it. Trinkety beeping noises scream at us all. It’s those automated grills and fryers behind the counter. Their sounds fill the space, which is already tapered off with caution tape and crammed with big puffy jackets. What’s going on?

“There was a fire here a couple weeks ago,” says Zayd as he stacks happy meal boxes into lengthy towers. He’s 20 years old and still has a pubescent mustache.

“The fryer caught on fire and burned a hole through the…through the roof. It was bad. That’s the old fryer over there. We gotta get a new one.”

He pauses the music in his airpods and tilts his chin towards the other end of the restaurant at an ambiguous black tarp sectioned off with caution tape. That area is usually full of people: hungry and satiated, drunk and sober, rich and homeless.

“I don’t see anything too crazy, just regular stuff like homeless people and all that: crack heads, fighting. Ain’t nothin too crazy to everyone round here.”

He digs into a big cardboard box with happy meal toys.

“Here, you want one?” he asks.

I smile at the green box and put it in my pocket. Zayd’s coworker walks by looking bored like a ten year old in an art museum. He slouches in one of the chairs and chuckles at us.

“Have you ever met a Penn student?” I ask.

“I don’t know no Penn students” he says. “They be coming here though… It ain’t no different from any other college. It’s a bunch of people from everywhere.”

He attended the Indiana University of Pennsylvania for a semester before dropping out.

“It was kind of weird cus everybody act different. Everybody was so friendly it made me uncomfortable.”

The computer beeps screech again. I wonder if the sounds bother him at all as he folds happy meal boxes or takes orders at the registers.

“Do you like it here?” I ask.

He looks down at the floor.

“Nobody wants to work here for life. If I had the freedom I wouldn’t work at all.”

His shift runs 7 p.m. to 4 a.m., six days a week. During the day he works at a retirement home.

“I don’t sleep a lot.”

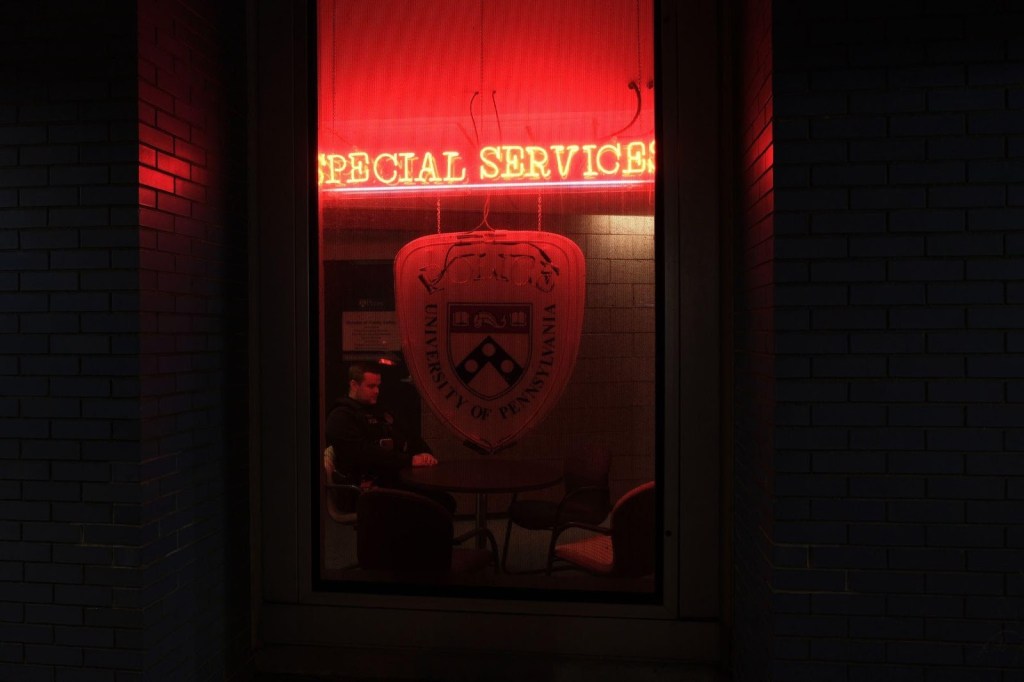

Harrison College House Lobby, 1AM

“I don’t even know what to say. I’ve been here since Sunday. And I could tell you, nothing seems different.”

The whites of Amber’s eyes start to glisten, then water. Amber is a pseudonym.

“It’s bad out here. I lost someone to suicide and I would have never thought.”

She sits up in her swivel chair and wipes the tears with her scarf. She’s in her mid-twenties, wrapped up head to toe in black Allied Universal gear. Not an inch of her light brown skin shows except for her freckled cheeks.

Five security guards declined to speak with me before I approached Amber at the wrap-around desk in Harrison, a highrise dorm built in 1970. She had arrived two hours earlier for her midnight shift and stood out with her sparkly headband warmer. A plastic barrier put up as a COVID precaution shields us from each other.

“I like the barrier,” she says. “I don’t really feel threatened by students here. But in the bar, people can become drunk and aggressive.”

She used to bartend early morning shifts before becoming a security guard. It was an underground job she took at the height of COVID restrictions.

“I couldn’t be a bottle service girl or server because there are no boundaries. Having that bar between me and the guest gives me more confidence… The kind of confidence you would get if you were in a fish tank in Times Square, you know?” I don’t really know.

“There are times where I look good and I feel good. I’m in the middle of the dance floor and well aware that everyone is looking at me. Throwing your hands in the air, losing yourself in a moment, the music. I love it,” she laughs. “Maybe it’s just liquid courage.”

But behind this barrier she’s invisible. From midnight to 8 a.m., she pays bills, watches movies, writes goals, manifestations, to-dos, lists of people she would invite to her future wedding and people she would break money to if she ever won the lottery.

“This shift is really dead so they don’t mind it.”

Normally she brings a journal, but tonight she’s using her phone. She hands it to me and scrolls rapidly through her notes app.

“Let’s see: redo bedroom, grocery lists, restaurant idea, Instagram palettes, summer goals 2023, karaoke ideas.”

“Karaoke?” I sit up and fold my legs.

“Yeah I wanna open up a karaoke bar and hookah lounge: Four rooms, $250 each, 8-10 people, charge $10 per extra hookah. This was made at 3:26 in the morning… On Halloween!”

She continues scrolling through her notes: Apartment ads, a new Range Rover, a Facebook post that says “I will be the first millionaire in my family.” Not too different from what I’d expect to see on a Penn student’s phone.

“Do you feel like you could be the first millionaire in your family?” I ask.

“That girl that is so confident on the dance floor could. This one that’s sitting here the whole fucking night? I don’t know.”

She starts playing with the ends of her hair, which used to be dyed red a few weeks ago. She redyed it black after her employers called it “unprofessional” and “loud.”

“Nobody can be their authentic self here,” she says.

Amber has a dozen tattoos hidden under her black uniform jacket. Some are meant to tap into her androgynous side like the one on her left arm: A woman with a boxing helmet and David Bowie stripe slashed across her face, cigarette in mouth. She tries to roll up her sleeves to show me, but it’s too long.

“I feel like it describes me; I’m just a beautiful badass.” If she ever made it big on TikTok, she knows that the world would see something of themselves in that glamor.

“My family knows I have it in me to be so confident. But I’m not sometimes.”

Two white couples walk into the lobby wearing slim black suits and colorful dresses. They look like they’ve come home from a Hollywood gala and mumble in Spanish. Amber turns around in her swivel chair to give them instructions on how to register guests into the building. One of the girls asks for a mask while the other wraps her arms around her date, swaying drunkenly with her eyes closed. They seem desperate to reach the elevators and as soon as they do, Amber swivels back to me rolling her eyes:

“Like I said, my family sees me as a super-uber overconfident person to the point that they can see me becoming a millionaire; they can see me doing things as wild or free as a playboy. They think that highly of me, but the students that come through here don’t see me. I’m invisible. I’m not worth the hi. Like in the situation you just witnessed, it could be so demeaning because they’re like ‘Come on, just sign us in, do your job.’ I’m like, you don’t even know my situation. I’m simply here to pay my bills. This is not my end all be all, so don’t treat me like I’m just some worker. I try to be nice, I try to say hi. But just imagine 20 students walking by. You say hi 20 times, and you don’t get a single one back.”

West & Down

There’s a line on 39th. It’s not crooked or straight, but sways with the pulse of music and breaks as bodies cut in. Heads doused in perfume turn toward each other blowing nicotine vapor and smoke. Fingers scramble through purses and wallets in search of driver’s licenses, foreign passports, spare cash. When Nasir raises his voice, the line stands on its tiptoes and turns to the front like a pack of meerkats. Nasir says, “straighten up”, and they straighten up. He folds fake IDs like cardboard and the line moves on. The 23-year-old bouncer of the West & Down nightclub is vigilant and assertive. No one gets in unless they comply.

“Basically, all that being a host requires is demanding money from people at a high level. I’m pretty good at it… Because I’m an asshole. I can be a nice guy, but for the most part I’m not. And here’s the other part. This life thing we got, it’s about balance, right? I would say that out of the 12ish security guards we have on the roster, I’m the least crazy in the entire room. Like these guys are fighters ready to jump off in a pack. It’s a gang mentality. And I’m the guy who has to tell people to relax. I bring that balance.”

On a cold afternoon, I meet up with Nasir and he shows me the main entrance to the club, which is hidden inside of a popular Korean restaurant called Bonchon. If you were to walk in for lunch, you would be greeted by a host before even noticing the underground doors shrouded in grates and fluorescent lights. At night, those lights shine blue in the restaurant lobby, but are nearly impossible to see from the street with the line packed around Nasir. Regulars dap him up from left and right. Stacks of cash bulge out of his pockets and strobe white from iPhone flashes. Inside the club there’s chest-pulsing hip-hop music, neon lights, dancers huddled in sweaty circles and pairs. Bartenders fling their arms from vodka to soda gun, plastic cup to soggy bills. Euphoria airs above the dance floor. Some sing at the top of their lungs, their out-of-tune voices drowned out by the speakers, while others stand in the back waiting desperately to pee. Anything could be happening in those stalls.

“When I first started a few months ago, I pretty much just watched the bathroom. I had to keep an eye out for drug use, make sure there was no intersexual stuff. Then over time, my role shifted to working the register; being a host.”

Nasir only started this job in August, but he’s moved quickly through the ranks and now oversees security from inside and out.

“There’s a lot of dumb shit that occurs at this door, bro.”

Fights, fake IDs, fake promotion flyers. He’s mostly dealing with Penn, Drexel, and Temple students; some even come from Villanova.

“It’s interesting. I’m only 23, so technically student aged. But I’ve always been kind of mature for my age too. So a lot of the things that I see happening in the club, I’m just like bro…what? [Shakes his head]. I’m just lost when I see random fights for no reason; excessive drinking. It’s all so silly to me.”

“How do you normally calm people down?” I ask.

“We don’t have guns. And putting our hands on people is not the go-to. So my role is to defuse situations. But I’m good at that anyway, it’s my life.”

Nasir’s role as a mediator at the club is really an extension of his life at home.

“My mom has issues that she hasn’t dealt with. And so the way she deals with anger and sadness, bitterness and resentment, it…” He rubs his fingers together. “Caused a lot of friction between us.”

They used to fight about little things like washing dishes and leaving their back door unlocked. Nasir moved into the basement to remove himself, but he could still hear it all.

“Upstairs, the fights between my sister and my mom were ten times worse than anything I went through. It’s just taxing. I tried to be a mediator but kind of realized that this shit is deeper than anything that I can really handle. They need to go see help.”

During the pandemic, Nasir’s best friend moved in, and the arguments shifted towards COVID rules and having friends over. Nasir previously worked at a nursing facility where he saw 60% of the residents pass away within two months, yet he remained skeptical of COVID’s transmissibility. Nasir’s mother didn’t feel the same. Their relationship reached a breaking point after a physical fight erupted, and he was left alone to take care of his sister.

“I had to make sure she took care of herself, bathed, kept her room straight. I tried to play the parent, but then I quit. Because that’s not my job, and there was still work to be done on myself. Mentally, I was fucked up.”

After midnight, Nasir works the door to another underground where humid air pulses the walls. Moving inside and out, it seems under control. But like a dream, it could fold any second. The room swells with pop beats, catharsis, moshing crowds.

“I’ve been having ‘meaning of life’ thoughts since I was seven years old. Like why are we here? What’s the purpose? Why does it matter? And every time I come to the conclusion that it don’t fucking matter. People wanna fight about whatever – These Russians and Ukrainian n****. All of that shit does not matter at its core. Nothing does. So if you wake up every day with that thought process, life is taxing as fuck like it’s hard to want to do things on a consistent basis. You know what I mean? You don’t wanna do anything but survive. So that’s what I have to release from: Knowing that shit don’t really matter so what are we really doing?”

“As I’ve grown older, I started to realize that not everybody has those opportunities to be able to process what they’ve gone through and then release it. So I come to a club with a whole bunch of college kids who are fresh outta their parents’ cribs, have had zero time to rectify all the trauma that they’ve been through, and they’re trying to figure out how to be an adult, pay for college. And now they gotta learn some shit. So when they come outside they just wanna let go of all that. I get it.”

I met Nasir on a Wednesday night. That Saturday, the club shut down for good.

“It’s NDA stuff” he says, so I don’t push for more.

“What was that last night like? What are you gonna miss the most?” I ask instead.

Nasir pulls out his phone and scrolls through his camera roll.

“Prior to getting this job, security guards were just security guards doing security things. And then I got this job with my main homie and we became the security guards that actually dance.”

He clicks play on a video and the music drops: Ice Melts by Drake. Dressed all black with 76ers sweatpants, he puts on a cold face. A friend watches close by.

“My energy is infectious,” he says.

His shoulders jerk, one arm in the air.

“I’m never the only one dancing”

His foot moves are airy, sneakers glowing. He points to himself..

“You see me, and you just have to dance.”

“Damn!” shouts the cameraman.

His friend gets involved and they break into laughter.

“Ey, don’t stop!” shouts Nasir on the screen.

“Now 75% of the security guards have at least tried to dance at some point. And that was a beautiful thing.”

The video ends.

“Damn, I’m gonna miss this place” he says, smiling at his phone.

“I didn’t realize how good I was at dancing until I came to the club and saw the reactions of people. It made me so much more confident.”

He recounts one night where his favorite DJ played trap music for the first time.

“I couldn’t stop dancing the entire night. He kept playing banger after banger after banger to the point where I had to go in the bathroom and take my work shirt off and bring it out to put under the dryer.”

He takes out his airpods as if the conversation is about to begin.

“There was another night when DJ Bry pulled up with the Philadelphia 76ers dunk squad! Now all of these guys are athletes but they can also dance cus that’s part of their job. You thought I was good, those guys are fucking different bro.”

His coworker challenged him to dance-battle the dunk squad, and he did.

“I won. 1000%.”

Harrison Lobby, 2AM

I return to Harrison a few weeks later. The fireplace is turned off tonight. I ask Amber if she’s ever left Philly.

“I went to St. Thomas once. It had the most amazing weather. Waking up in that type of environment I thought how could you ever be sad? But it’s not home. Like I can’t get a cheesesteak around the corner. I can’t just pull up on my cousin’s.”

Her smile widens.

“As a young Black girl, there is like a certain culture. Meek Mill has a song called ‘Oodles O’ Noodles Babies’. It’s the pack of ramen noodles you get for like 25 cents at the store. And it’s just a staple for growing up in Philly. Like, if you were a young Black kid you grew up on that stuff. There’s a certain culture with being raised here. Like you’re gonna pass somebody that might not talk like you, look like you, dress like you. But somehow, someway, something links y’all because y’all from here.

“Do you think Penn feels like Philly?” I ask.

“I mean, Phil-a-del-ph-ia, the City of Brotherly Love, the Independence Hall, the book—the textbook Philly, sure. But the one I’m used to, the culture, no. Definitely not.”